As one of the world’s fastest-growing economies, India aspires to become a global manufacturing hub, thus reducing its reliance on external actors, particularly China. In 2020, Indian Prime Minister Modi launched India’s Atmanirbhar Bharat program (Self Reliant India), to reduce foreign dependence and promote domestic production in strategic sectors. Theoretically, this should result in a decline in the share of Chinese inputs in Indian industrial production. However, evidence suggests otherwise.

The following lines attempt to show the growing paradox within India’s industrial policy: although the government appears to have placed a growing focus on self-sufficiency, India’s dependence on Chinese imports has not diminished, on the contrary, it has intensified in several sectors. Particularly, a significant reliance on China for essential inputs can be seen in four major industries: pharmaceuticals, chemicals, capital goods and machinery, and electronics. The question is: to what extent do Indian industries depend on Chinese exports, and which stages of their production processes are most reliant on Beijing? The findings provide insights on the structural barriers to decoupling and the complexity of building industrial autonomy in an era of global interdependence. Consequently, today Atmanirbhar Bharat can be considered more of a strategic aspiration than an economic reality.

The dire economic situation of the early 2010s in India required strong policies to stabilize institutions and stimulate growth. Thus, Prime Minister Modi enacted the Make in India initiative in 2014, focusing on reducing red-tape barriers, strengthening local infrastructure, and embracing foreign investment. However, due to economic dependency on foreign actors, especially China, the modernizing and developmental push switched to a rhetoric of self-reliance with Atmanirbhar Bharat in 2020. Ten years after the launch of the Make in India initiative, the Ministry of Commerce and Industry evaluated the program, demonstrating significant growth in multiple sectors, especially electronics, while non-governmental sources were more sceptical of this growth.

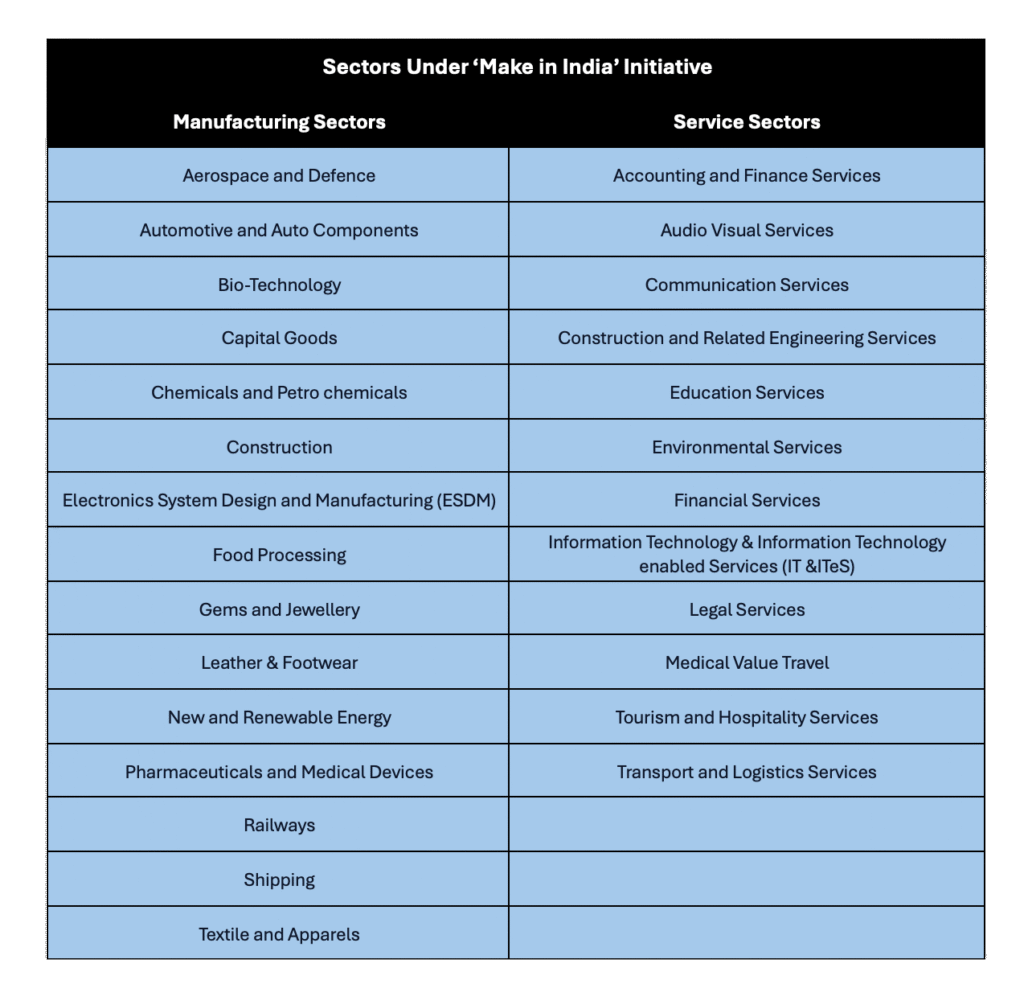

Make in India indeed involves a large array of sectors, both in Manufacturing and Services, and throughout the years have been backed by several key programs, such as: the Production Linked Incentive (PLI) Schemes, that covered 14 strategic sectors in order to foster investment and boost local manufacturing; the Semicon India Programme launched in 2021, a $8,69 billion programme to develop an Indian semiconductor ecosystem.

Unbalanced relation

A first indicator of dependency can be found in trade relations. In 2023 China has become India’s largest trade partner, overtaking the US. Bilateral trade between India and China has constantly grown since the beginning of Make in India, with imports from China being the main component: $101.7 billion in 2024, in comparison to $65.2 billion in 2020, which together with a constant rate of exports throughout the period, led to an increased trade gap of $85 billion ($48.6 billion in 2020). China alone represents more than 15% of India’s total imports.

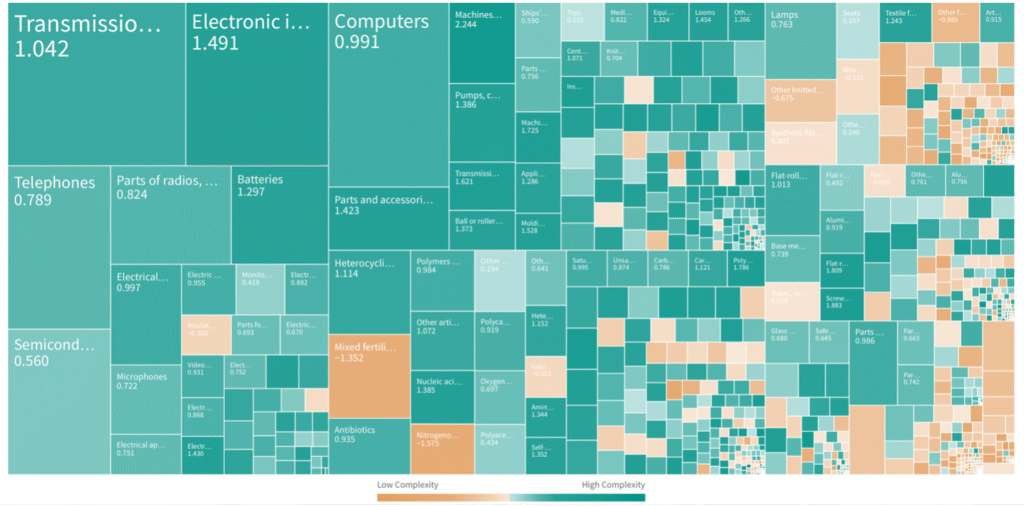

However, trade data, barely scratches the surface of Indian industrial overreliance on its main partner. It is much more revealing to look at what is being imported. We will have to go into detail of the sectors that drive Indians exports, and their upstream goods. We can assess the complexity of imports for products with higher technological and research content. In this, we make use of a very useful tool developed by the Harvard Observatory, which examines the economic complexity of trade. In this case, we can observe the complexity index of Chinese products imported into India, for a total value of $121 billion. We can note how the vast majority of the main imported industrial goods are of high complexity, thus indicating a low local added value of Indian supply chains.

“Today around 80% of India’s API needs are imported, with over two-thirds coming from China.”

Third in the world for manufacturing volume, the pharmaceutical sector is certainly a domestic excellence. The wide range of products includes generics, OTC drugs, vaccines, biosimilars, and biologics. The Indian pharmaceutical sector currently accounts for 20% of drug exports and will reach a value of more than 130 billion by 2030.

This expansion coexists with a structural vulnerability: dependence on foreign sources for APIs (Active Pharmaceutical Ingredients). India was mostly self-sufficient in terms of formulations and ingredients in the 1990s, but today it imports around 80% of its API needs, with more than two-thirds coming from China. The primary factors driving this trend are India’s domestic specialisation in generics rather than proprietary medications and China’s 20–30% lower production costs than India. Recent studies show that dependence remains high: imports of antibiotics rose to $1,271.4 million (+130.7%), with Beijing share reaching 81.7%. Despite public initiatives, purchases from China continue to grow, driven by established supply chain advantages.

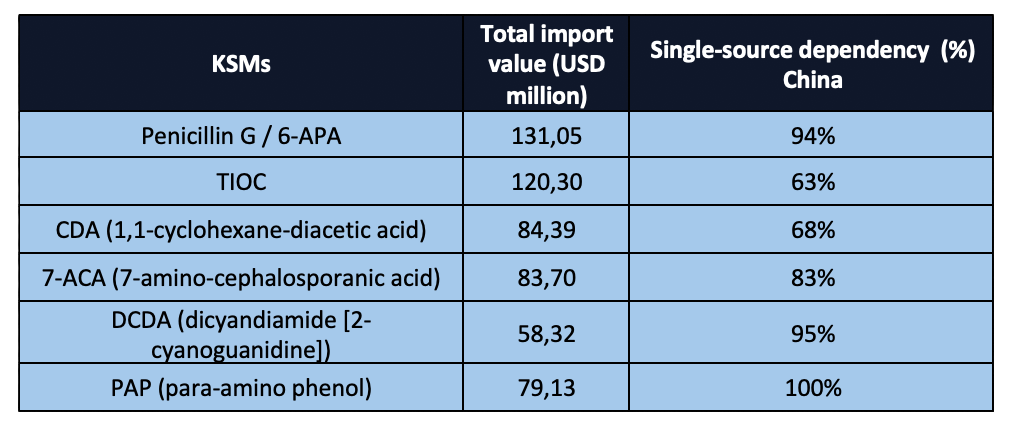

The paradox is particularly evident in the case of Key Starting Materials (KSMs) covered by the Production Linked Incentive (PLI) scheme, where, despite government efforts, the over-reliance on China remains clear.

The main reason for this inability to decouple lies in research: Indian companies generally allocate 5–10% of their revenues to R&D, a share lower than the global average of 27% in biopharmaceuticals and than the levels of the United States (34%), Europe (22%), and the Asia-Pacific region (20%). This results in a dual challenge: reducing dependence on critical foreign inputs and increasing research intensity, so as to sustain competitiveness and make the expected growth of the sector more resilient.

“Between 2007 and 2022, chemical imports from China increased by 296%, reaching 17.4 billion dollars.”

The chemical sector is one of the main drivers of the country’s exports and plays an enabling role for other sectors, but at the same time the chemical industry shows the same pattern as the pharmaceutical one. Between 2007 and 2022 imports from China increased by 296%, reaching 17.4 billion dollars. Beijing supplies organic chemicals, dyes, fertilizers and other essential inputs for agriculture, healthcare and manufacturing—a configuration that increases exposure to geopolitical risks and possible disruptions of supply chains.

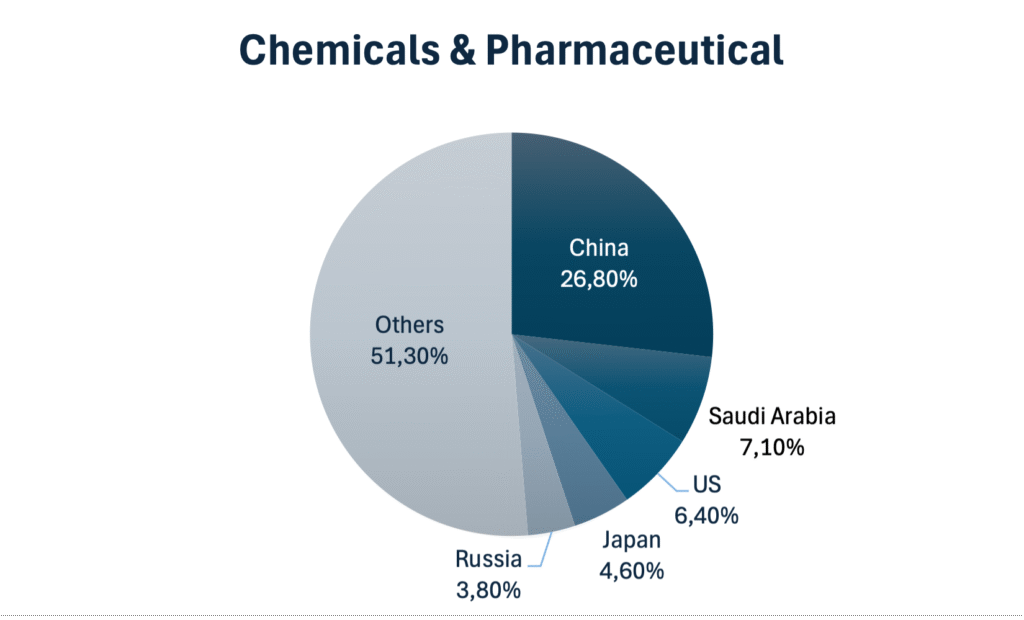

In this sense, the sector not only contributes significantly to exports and employment, but also supports critical functions such as pharmaceutical production and agricultural productivity; precisely for this reason, the growing dependence on Chinese imports represents a strategic vulnerability. Considering chemicals + pharmaceuticals together, imports exceeded 54.8 billion dollars in 2024; between 2007 and 2022, China’s share of Indian imports of these materials increased from 18% to 29% (+56.4%), while in value terms imports rose from 4.4 to 17.4 billion dollars (+296%). In 2022, Indian imports of chemicals and pharmaceuticals totaled 76.94 billion dollars, with China accounting for 26.8%.

Entering into detail of key products:

- Organic chemicals imports skyrocketed by +330.3%, from 2.6 billion in 2007 to 11.2 in 2022. China’s share of the pie consists of 44.7 of organic chemicals, which are essential for pharmaceuticals and fertilizers.

- Fertilizers went from 822.4 million to 2.23 billion dollars (+171.5%) whith China’s share growing from 11.1% to 20.0%. The increase directly affects agricultural productivity and food security.

- Dyes, paints, enamels, and inks went from 134.5 million to 771.6 million dollars (+473.6%); China’s share from 16.7% to 33.4%. These are crucial materials for textiles, printing, and coatings.

Made in In… China Machinery?

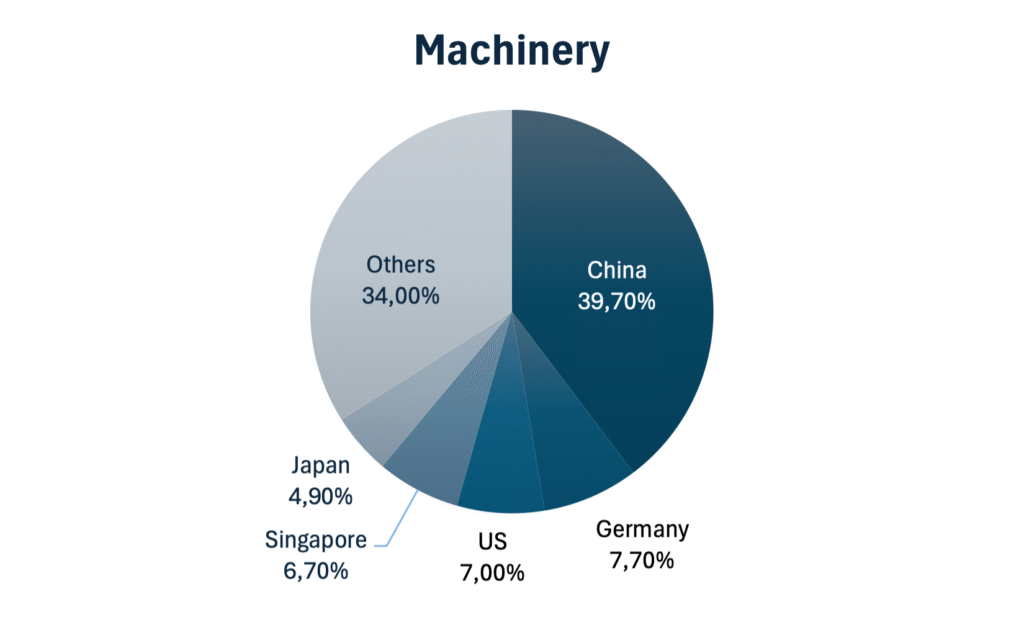

The Dragon’s footprint is also present in the machinery sector, where India’s technological gap has made it heavily dependent on Chinese supplies. In the last two decades, Indian machinery imports from China increased by 232.9%. If we compare the last decade with the precedent one, purchases from China jumped from 5.4 to 18.0 billion dollars; in 2022, the value of Indian imports exceeded 54 billion dollars, 39.7% of which came from China.

This trajectory is accompanied by fluctuating domestic performance: the production of capital goods oscillated between 2020 and 2023, before registering robust growth in 2024. However, a structural issue remains: due to technological gaps, the country continues to import the high-end machinery necessary for advanced manufacturing, which makes it difficult to internalize production.

High-end technology remains a Chinese prerogative

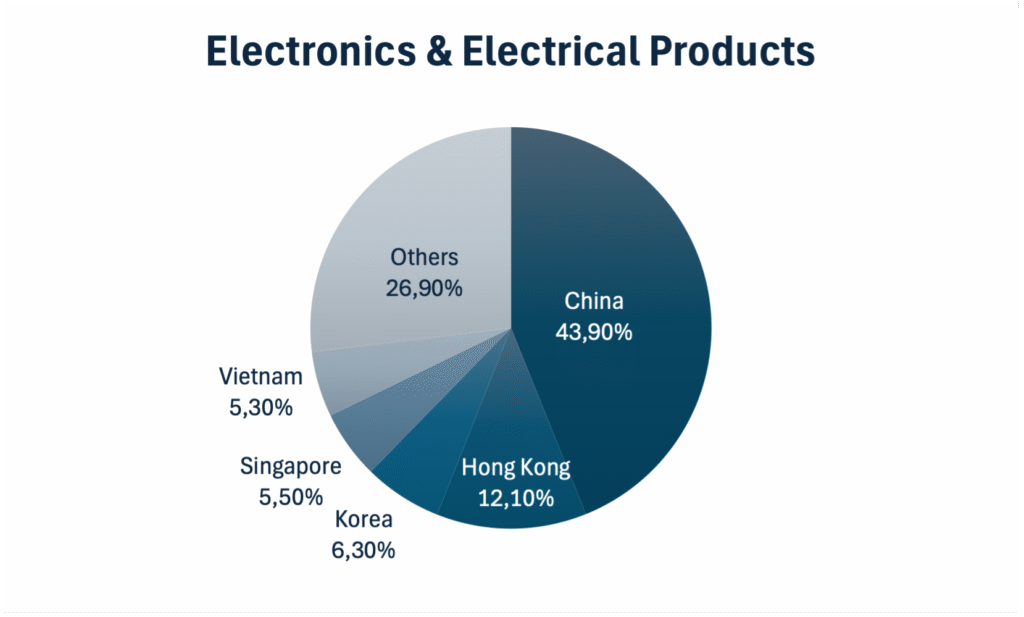

In the electronics/telecommunications/electrical engineering sector, India shows the strongest dependence on China. In 2024, imports reached 89.8 billion dollars; China alone accounts for 43.9%, while the combination of China + Hong Kong exceeds half of the total. Production gaps in semiconductors and lithium-ion batteries remain wide: Beijing holds 67.5% of India’s imports of diodes and transistors, and India produces less than 25% of its own Li-ion battery needs. This configuration, in an industry still focused on assembly, also affects innovation capacity and technological sovereignty.

Product data confirms the pattern:

- Integrated circuits: imports increased from $166.1 million (average 2007–2010) to $4,178.2 million (2020–2022), equal to +2,415.1%; China’s share from 19.2% to 33.4%.

- Communication devices (phones and wireless): imports at $3,691.1 million, with more than half of the market dominated by China.

- Diodes, transistors, and related semiconductors: from $113.3 million to $2,334.8 million; China’s share at 67.5%.

Overall, the increase in volumes and the concentration of supply on China/Hong Kong has made the supply chain more vulnerable, reinforcing the urgency to diversify sources and to enhance domestic capacities along the phases with higher technological content.

To sum up

India’s ambition to become a self-reliant industrial power, under the Atmanirbhar Bharat doctrine, faces a big obstacle, India’s heavy dependence on China. As evidenced by the data, the production of several important products, especially APIs, organic chemicals, capital goods, semiconductors, and lithiumion batteries, remains deeply tied to Chinese supply chains. Although India has attempted to break away from reliance using policy tools, like PLI schemes and import substitution, its efforts have been limited by gaps in technological capabilities, infrastructure, and R&D investment. The contradictions within India’s industrial trajectory point to a larger paradox: while the rhetoric of decoupling recurs in political discourse, the material reality of supply chains continues to bind Indian industries to Chinese inputs. Similarly, while the 2020 limits were successful in lowering Chinese investments in India, they have resulted in the suspension of critical projects due to a shortage of finances. This highlights the risks of Indian self-reliance doctrine, which must navigate a delicate balance between economic autonomy and continued development. The changing geopolitical scene may introduce an additional element of turmoil. While US tariffs create new competitive opportunities for India, they also risk making the country a dumping ground for Chinese surpluses.

India’s industrial dependence on China is a structural element of the country, and as such it cannot simply be eliminated through policies like Make in India, but requires technological and capital gaps to be addressed domestically.

Until this can be done, the Atmanirbhar Bharat doctrine will likely remain more a political aspiration than an achieved economic transformation.

Bibliography

- Akash Podishetti. (2025, April 3). Trump’s tariffs hit China harder, but can India bask in the dragon’s pain? The Economic Times; Economic Times. https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/markets/stocks/news/trumps-tariffs-hit-china-harder-but-can-india-bask-in-the-dragons-pain/articleshow/119939454.cms?from=mdr

- Bureau, P. C. (2024, June 22). India struggling to free pharma industry from dependence on Chinese APIs | Policy Circle.

https://www.policycircle.org/industry/apis-import-depencence-on-china/ - Choudhury, S. D., Dawar, T., & Bhambhani, S. (2025, April 15). India Navigates Trump’s Tariffs with Caution and Concessions. Asia Pacific Foundation of Canada. https://www.asiapacific.ca/publication/india-navigates-trumps-tariffs-caution-and-concessions.

- Ghosh, A. (2021, July 3). CSIR working on making 56 bulk drugs in India as Modi govt wants to cut imports from China. ThePrint.

https://theprint.in/health/csir-working-on-making-56-bulk-drugs-in-india-as-modi-govt-wants-to-cut-imports-from-china/688741/ - Government of India. (2025). Economic Survey 2024-2025. https://www.indiabudget.gov.in/economicsurvey/

- Government of India. Make in India: About. Make in India. https://www.makeinindia.com/about

- HarvardGrwthLab. (2020). The Atlas of Economic Complexity. https://atlas.hks.harvard.edu/explore/treemap?exporter=country-356

- India Exim Bank. (2024). Export—Import Bank of India (Annual Report 2023-2024). Bank of India.

https://www.eximbankindia.in/assets/pdf/public-declarations/1-FY2023-24-Annual-Results-13052024_Final.pdf - Malinbaum, S. (2025). India’s Quest for Economic Emancipation from China. (145). Asie.Visions, Ifri.

https://www.ifri.org/en/papers/indias-quest-economic-emancipation-china. - Memedovic, O., & Sturgeon, T. (2020). Mapping global value chains—Intermediate goods trade and structural change in the world economy.

- Ministry of Commerce & Industry. (2024, September 25). Make in India 2.0: Transforming India into aglobal manufacturing powerhouse. Government of India. https://www.pib.gov.in/PressNoteDetails.aspxNoteId=153203&ModuleId=3®=3&lang=1.

- Neumann U, Martin S, & Chandra A. (2024). Research and development (R&D) investment by the biopharmaceutical industry: A global ecosystem update. Johnson & Johnson, Titusville, NJ, USA; Harvard University, Cambridge, MA, USA.

- OECD. (n.d.). Trade in value-added [Dataset]. https://www.oecd.org/en/tiva.html

- Prakash, A. (2024). GVC Mapping for ASEAN and India (No. 24; ERIA Research Project Report). ERIA.

- Rajesh Kumar Pandey, & Tyagi Modh. (2025). A Case Study on Pharmaceutical Sector: Indian Context. https://doi.org/10.5281/ZENODO.14728984

- Rajeev Jayaswal. (2025, April 5). India to step up vigil on Chinese imports after US tariffs. Hindustan Times. https://www.hindustantimes.com/india-news/india-to-step-up-vigil-on-chinese-imports-after-us-tariffs-101743877993464.html

- Ray, D. S. (2021). Global value chains in the pharmaceutical sector. Project for Peaceful Competition. https://www.peaceful-competition.org/pub/crd4jweh/release/1

- Siddiqui, A. (2024, December 31). Indian Pharma Hits R&D Salvo. https://www.biospectrumindia.com/features/18/25489/indian-pharma-hits-rd-salvo.html

- Srivastava, S. (2025, April 28). Chinese firms turn to Indian exporters to help fill US orders. The Economic Times; https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/economy/foreign-trade/chinese-firms-turn-to-indian-exporters-to-help-fill-us-orders/articleshow/120681190.cms?from=mdr

- Srivastava, A. (2024). An Examination of India’s Growing Industrial Sector Imports from China. Global Trade Research Initiative.

- Team India Tracker. (2024, August 7). NITI Aayog member proposes partnership with China to cut down imports: A look at India’s import dependency on China. https://www.indiatracker.in/story/niti-aayog-member-proposes-partnership-with-china-to-cut-down-imports-a-look-at-indias-import-dependency-on-china

- Tewari, M., & Guinn, A. (2017). Leveraging Global Production Networks: Evidence from the Vizag Chennai Industrial Corridor. SSRN Electronic Journal. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2979109

- Upadhyaya, K. (2025, May 5). Why U.S. Tariffs Can Be an Unlikely Opportunity for India. The Heritage Foundation. https://www.heritage.org/trade/commentary/why-us-tariffs-can-be-unlikely-opportunity-india

- Venugopal, V . (2025, April 11). India rebuffs China’s BYD as Trump trade war creates openings. The Financial Times. https://www.ft.com/content/323784f9-3849-448d-a1d0-f3e1fd9b397b.

- World Trade Organization. (2020). Shifting patterns in trade. In World Trade Organization, World Trade Statistical Review 2020 (pp. 32–59). WTO. https://doi.org/10.30875